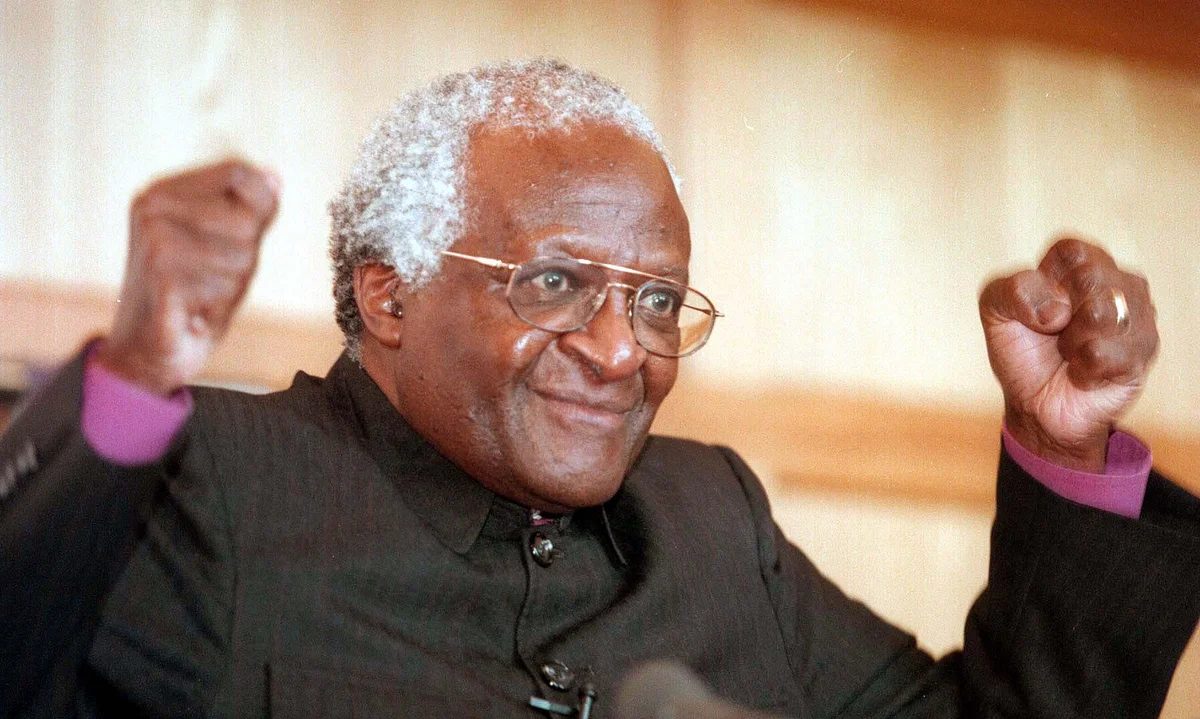

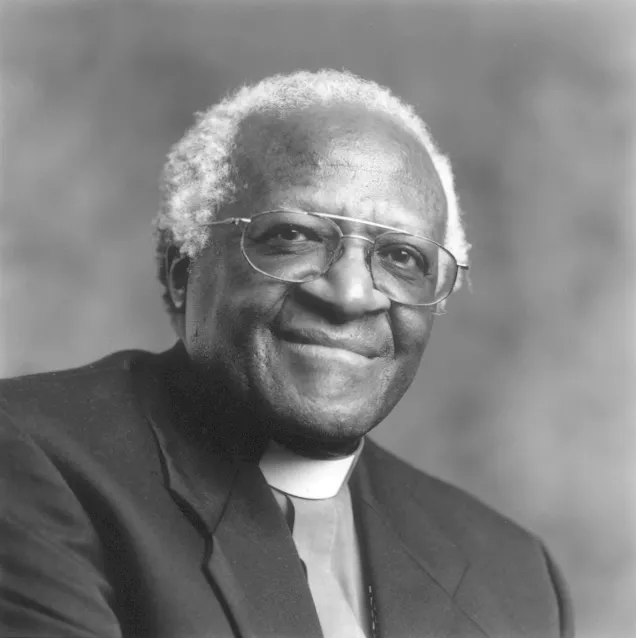

Before his death at the age of ninety, Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu asked to be cremated with water. It was, for many readers of the late-2021 headlines, an unfamiliar phrase—one that sounded more like a metaphor than a practical instruction. But for Tutu, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and lifelong advocate for justice, the choice was obvious. He wished to align his final act with his environmental and religious convictions. Characteristically, considering his life, he wanted to use the moment to call attention to the moral blind spots incurred when we accept some practices as normal and others as abnormal.

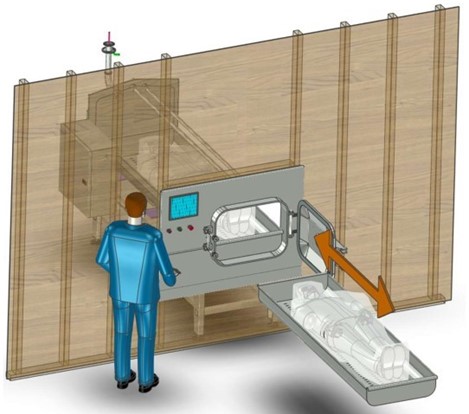

The method Tutu chose for his body after he passed is called alkaline hydrolysis—also sometimes called aquamation—and uses a heated bath of water and alkali to accelerate the natural breakdown of the body. The process has been around for decades in medical and veterinary contexts, but is only recently making its way into public options. Georgina Robinson, a scholar of death studies at Durham University who has conducted ethnographic fieldwork on the technology, notes that public uptake often follows a familiar pattern: first the environmental benefits become apparent, and then the realisation that water may carry both preferential and symbolic weight for many people.

For Tutu, the environmental case was plain. Burial and flame cremation, the two dominant forms of disposition in much of the world, are resource-intensive to the point of absurdity. Shashi Pathak and Richa Mishra, who study ritual ecologies, such as death practices, at Nirma University in India, estimate that industrial burial in North America consumes millions of gallons of embalming fluid and vast quantities of steel, concrete, and timber every year; this is on top of the land use that cemeteries occupy. Cremation, meanwhile, pumps hundreds of pounds of carbon dioxide into the air with every body burned, along with mercury and other potential pollutants. By contrast, alkaline hydrolysis uses up to 90 percent less energy and produces no airborne emissions.

The choice for Tutu may also be understood through a theological frame. As an Anglican archbishop, Tutu would have recognised the resonance of water in Christian tradition: as the force of baptism, creation, and renewal. In Robinson’s research, beyond religious perspectives, many families described the idea of their loved one being aquamated as intuitively gentler than fire—something that frames death as less than an act of destruction or loss but as a return.

The philosopher Geoffrey Scarre, who has written on respect for the dead, argues that the ethics of body treatment after death are not just about what we do with the remains but whether the choices align with the life and values of the person who has passed. In this light, Tutu’s aquamation was a coherent extension of his moral identity. His decades of anti-apartheid activism, his advocacy for reconciliation, and his environmental stewardship were all expressions of the belief that personal dignity is inseparable from both our shared dignity and the shared Earth.

Death studies scholars have begun to call these alignments death-styles—posthumous practices that mirror the values of one’s life. Robinson suggests that through figures like Tutu, aquamation is not a standalone gesture but part of what the environmental philosopher Aldo Leopold might have recognised as a land ethic applied to the self. Choosing water over fire, Tutu also enacted what Robinson describes as the convergence of life- and death-styles: the extension of an ethic towards the most intimate personal act.

This is not, however, a choice without cultural resistance and constraints. In many places, aquamation remains illegal or is complicated by regulatory ambiguity. According to Aimee Sheetz, a legal scholar at Cleveland State University who has tracked U.S. state-level debates around aquacremation, opposition often comes from industry actors invested in existing infrastructure or from groups concerned about the perceived indignity of disposing of the liquid effluent remains. Yet Tutu’s public embrace of the process offered something few discussions in this realm do: a vivid, morally legible example.

In this sense, his final act was a sermon without words. It challenged the inertia of habit, invited reconsideration of what counts as respectful, and suggested that even our exits from the world can be shaped by care. As climate change accelerates and the environmental costs of death treatments become harder to ignore, Tutu’s decision stands as both a model and a provocation. It asks whether we are willing to extend our stewardship not only over the land we inhabit, but over the ways we leave it.

References

Arnold, M., Kohn, T., Nansen, B., & Allison, F. (2024). Representing alkaline hydrolysis: A material-semiotic analysis of an alternative to burial and cremation. Mortality, 29(3), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2023.2174838

Crethers, G. (2022). Desmond Tutu (1931–2021). History in the Making, 15(1), 245–249. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol15/iss1/13

Matende, W. (2022). An ethical assessment of current death disposal beliefs, attitudes and practices in Gaborone’s Ledumang ward in Botswana (Master’s dissertation, University of Zambia).

Olson, P. R. (2014). Flush and bone: Funeralizing alkaline hydrolysis in the United States. Science, Technology & Human Values, 39(5), 666–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243914530475

Pathak, S., & Mishra, R. (2025). Ritual ecologies: Analyzing the environmental impact and cultural sustainability of death practices across civilizations through selected case studies. EPJ Web of Conferences, 328, 01063. https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202532801063

Robinson, G. M. (2023). Alkaline hydrolysis: The future of British death-styles [Doctoral thesis, Durham University]. Durham E-Theses. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/15085/

Robinson, G. M. (2025). Alkaline hydrolysis and its affordances. Mortality. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2024.2445852

Scarre, G. (2025). Alkaline hydrolysis and respect for the dead: An ethical critique. Mortality, 30(1), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2024.2338284

Sheetz, A. (2023). A call for the legalization of two sustainable means of final disposition in Ohio. Cleveland State Law Review, 71(3), 915–940. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol71/iss3/12